The paper Thinking Philosophically About Teaching is by Gert Biesta and Barbara Stengel who from the outset make clear that philosophic enquiry is a form of research. [1]

The paper sets about examining what teaching is and should be. [2]

In this way much of the current debate about teaching, reduced as it is to a binary choice between teacher as facilitator and teacher as direct instructor, becomes puerile and just so much chatter. Just scroll down to my previous blog to appreciate how inadequate and destructive such thinking is.

A key point in Biesta and Stengel’s argument is that teaching is relational. They write:

‘Teaching is always relational in which there are ‘… dimensions of power and desire invoking a vision of moral interaction made concrete in the authority of the teacher.’ [1]

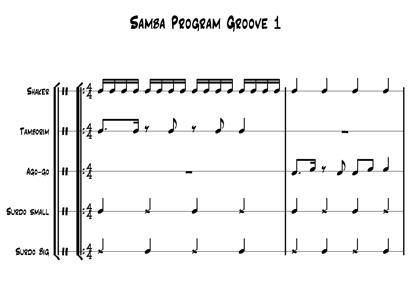

We see this below in the example of a music teacher teaching music.

Just one icon of music teaching. [3]

‘Mid-day Saturday and 23 young people aged 8-13 have come to make music together in the large hall come gymnasium.

Chairs are being set out in a circle. It is the Creative Orchestra. There are violins, saxophones, clarinets, pianists, percussionists in equal numbers; harpist, bass guitarist, acoustic guitarist, cellist, trombonist and flautist. And a teacher who I sense will be a quiet presence with a clear voice of authority and who knows a lot about attunement.

Still encumbered with bags and not all instruments are ready. A quiet word to move bags to their place and we are into a round the circle warm up, ‘remember to keep it flowing’: the leader sets the round in motion with a simple four beat rhythm clapped, class copy then the first solo from Peace, all copy and so on yielding 23 rhythmic ideas, ever more intricate and calling for ever more attentive listening.

And that’s how the session moves forward – everybody learning to listen, having ideas, making suggestions, having thoughts; everybody with a part to play in what is made together today with the leader ready to offer stimuli, and who leads how I had imagined, gently attentive to fresh thinking, new possibilities. The stylistic generator is a group of Samba grooves

And then there is a counterpointing pentatonic melodic framework set out in the centre of the circle; D E G A B represented by five spaced objects.

E has a big box, for E is to be our tonal centre. The class are shown how by stepping between the tones the melody is made and how a repertoire of signals calling for variation in durations and dynamics can be used. And before long the class are rehearsing how to make notes really short, notes that grow louder and then as players volunteer to lead, so more possibilites emerge to be thought about.

‘Any suggestions, thought, ideas’, asks the teacher. Some suggestions come fully formed, some convoluted, some tongue-tied inviting others to articulate more clearly before reaching their final form in the music. What a long way words can be from music.

An important part of the process is the assembling of the material into a work in progress that we can all be inside for a few minutes. Then more thoughts, ideas, suggestions.

The class are relaxed about all this. They are learning to be still, thoughtful, circumspect, wondering, some just being, barely becoming so it seems. The harpist seems happy enough to be there with her harp. Time is not rushing on. There is none of that ‘fast pacey please the inspector stuff’ here, rather staying with the moment, indwelling the music. Rapid progress is a stranger here, slow learning a virtue.

Ibrahim take a lead and tells us that we can think of the music as being like a journey. Ideas are flowing faster now with contributions from Peace, Oscar, Neoma, Jo and Jessie. More leaders in turn take centre stage and confirm this way of working, expand tonal and rhythmic possibilities calling for music made with intention as well as deliberation.

The rhythm section is strong, rarely lose their grove. Frederick takes time out to teach Joe how his cabassa part should go and this is in the middle of a six minute playing.

Now Oscar suggests combining four ideas to add to the advancing sophistication of what is not actually a piece of music, rather a series of sketches that might become a piece.

The teacher, for the first time mindful of the time, for there is a time to end the session, says, ‘seven minutes to go’ and Oscar leads the final excursion.

‘It’s a journey to an unexpected island’, says Naomi.

We are now well into the afternoon on this dull Saturday in June, it’s time to go home. Chairs away. With repose and a simple satisfaction, so it seems, the children go their way.

I wonder what will happen when the choir join the orchestra next week?’

Notes:

[1] https://www.google.co.uk/search?source=hp&ei=I_iEXN-qN8K4kwWzx7KQCw&q=thinking+philosophically+about+teaching&oq=Thinking+Philo&gs_l=psy-ab.1.3.0l6j0i22i30l2j0i22i10i30j0i22i30.5158.14682..18866…0.0..0.71.926.15……0….1..gws-wiz…..0..0i131j0i10.bEF0zwNDJQs

In the present time it is easy to imagine that educational research is the fiefdom of empirical studies where cognitive psychological theories of learning underpin what can be known and what can inform what works in the classroom.

[2] As part of the argument six teacher icons are presented: Plato’s dialogic questioner, Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s responsive (and autonomy-seeking) tutor, John Dewey’s democratic designer, Paolo Freire’s liberator, Jacques Ranciere’s critical egalitarian, and Nel Nodding’s carer.

[3] A version of the teaching sequence featured in the blog The Creative Orchestra. https://jfin107.wordpress.com/?s=tHE+cREATIVE+oRCHESTRA